In 1995, McArthur Wheeler and Clifton Earl Johnson robbed two banks in Pittsburgh. They believed they wouldn't be caught because they had researched how to render themselves invisible to bank security cameras. They learned that lemon juice could be used to write an invisible message on paper that could only be made visible by heating up the paper. Could lemon juice make them invisible to bank cameras? They conducted an experiment: they rubbed lemon juice on their faces and took a Polaroid picture -- their faces did not show up on the Polaroid!

They rubbed lemon juice on their faces, wore no masks, and robbed the two banks at gunpoint. The Pittsburgh Police showed the security camera images on local TV, and they were soon apprehended. They were nonplussed and insisted the police had no evidence. It is unknown why the Polaroid failed to show their faces - perhaps defective film or perhaps they pointed the camera in the wrong direction.

The Dunning-Kruger Effect

David Dunning read about the case. He hypothesized that if Wheeler was too stupid to be a bank robber, he may have been too stupid to know that he was too stupid. Dunning and his grad student, Justin Kruger, wrote a paper titled "Unskilled and Unaware of it: how difficulties in recognizing one's own incompetence lead to inflated self-assessments." This is known as the Dunning-Kruger Effect.

Dunning and Kruger found that people who first start to learn about any subject have an inflated perception of how much they know. Paradoxically, when people learn a lot about a subject, they think they know less about it than they actually do know. The following (exaggerated and comical) chart sums up their findings. Dunning-Kruger didn't use terms like "Mt Stupid" or "Valley of Despair." As people start to learn about a subject, their confidence in their knowledge is never higher. If they learn more, they quickly learn how little they know about it. If they stick with it and learn even more, they slowly gain confidence in their knowledge. But they will never have as much confidence as they had initially - they have humility because they have learned how much they don't know, and perhaps can never know.

A Personal Journey from the Peak of "Mt. Stupid"

I wanted to write a novel about an ancient virus that gets unleashed because of global warming. The idea was that the virus evolved before there were humans, so that we had no natural immunological defense to it. It was responsible for killing off all placental mammals in Australia, so it would kill many hundreds of millions of people, not to mention the animals humans use for food and pets. I wanted it to be plausible - how hard could that be?

I studied virology, epidemiology, genomics, and immunology, and found I understood only a small fraction of what I read. Just learning the basics in those fields with no educational background was difficult. After a year of studying, I hadn't solved the problem of making it plausible.

Retroviruses, endogenous retroviruses, virosomes, proto-oncogenes, endosymbiotic theory, maladaptive mutation, viral reservoirs and vectors, carcinogenic viruses, telomeres, zinc fingers, morpholinos, surface proteins, dysfunctional micro-RNAs, antagomirs, DNA sequencing, epigenetics, trophoblasts, choriocarcinoma... After a year, I was ready to give up. I put the book on the back burner, but continued to do research as time permitted.

Five years later, I finally finished Thaw's Hammer. My current feeling is that it is plausible if one doesn't know too much. I think a true virologist would have many valid objections. I would rate myself about 10% of the way up the "slope of enlightenment."

One benefit for me was that when the pandemic hit, I knew enough to respect the experts in the field like Anthony Fauci. I also knew enough to laugh at the dangerous stupidity of anti-vaxxers like Jenny McCarthy, RFK Jr., and Joe Rogan.

The Salience of Socially-Derived Knowledge

People are political and get their information from "epistemic bubbles" or "echo chambers" of people who are politically similar. Because politics are increasingly polarized, there is a social disincentive to get down from "Mt.Stupid" where their peer group is. The authors found no correlation with degree of education -- educated people were as likely to be wrong as less well-educated people.

Humans are social creatures and get our opinions from our social peer group. Alienation from our peer group and their approbation is more important than error correction. Because of this, social media is now our primary source of knowledge. We have come full circle from the Stone Age when interpersonal gossip told us everything we had to know.Yuval Harari wrote about human evolution due to gossip in his book Sapiens:A Brief History of Humankind:

“Social cooperation is our key for survival and reproduction. It is not enough for individual men and women to know the whereabouts of lions and bisons. It’s much more important for them to know who in their band hates whom, who is sleeping with whom, who is honest and who is a cheat. This information about which individuals could be trusted — in other words, gossip — allowed early humans not only to survive, but also to expand their tribes. Long hours spent gossiping helped the early humans to forge friendships and hierarchies, which, in turn, helped to establish the social order and cooperation that eventually set them apart from the rest of the animal kingdom."

Homo Sapiens has always gossipped about people we know, come into direct contact with, or influence our survival (e.g., kings, lords, military, religious or political leaders). In the 18th and 19th centuries, society gossip became fashionable. A new target of gossip emerged in the early 20th century -- movie stars. Photoplay, one of the first movie fan magazines, began publishing in 1911, and provided gossip about all the silent movie stars. Studios were happy to add content, often fictitious, if it drove fans to the movies. Mainstream media began unabashedly adding gossip columnists: Hedda Hopper and Louella Parsons were top journalists in the 1940s and 50s. Hedda Hopper was a fan of Joseph McCarthy and often exposed Communists in the film industry. Confidential (1952) offered fans salacious content, not provided by the studios, and had an even weaker link to truth. Tabloids emerged with The National Enquirer in 1962. When Carol Burnett sued them in 1976, the Supreme Court affirmed that libel was not protected speech, and the tabloids started being more careful about what the presented as "facts."

Television brought stars into people's homes. Talk shows became the media for celebrity gossip. Joe Franklin (1951) was the first. The Tonight Show began in 1954 with Steve Allen, followed by Jack Parr, Johnny Carson, Jay Leno, Conan O'Brien, and Jimmy Fallon. It is the longest running show on television, and there are too many imitators to mention. Not only TV, movie, music and political celebrities, but interviewers became celebrities in their own right. Talk shows made people watching feel like they personally knew whomever was being interviewed as well as the interviewer. All these people entered our "epistemic bubble" and became arbiters of "truth" because of the "availability heuristic" (see below).

Social media started on the Internet in the early 2000s. LinkedIn (2002), Facebook (2004), YouTube (2005), Twitter (2006), Instagram (2010), Snapchat (2011), and TikTok (2017) quickly became the source for gossip for about 5 billion people worldwide. Not only do they reach most people on Earth, most people look at multiple platforms frequently throughout each day. The average consumer looks at social media for about 150 minutes every day.

Unlike published media, social media is not constrained by libel laws in the US. In 1996, Congress passed the Communications Decency Act. Section 230 carves out an exception to libel laws for owners of Internet platforms. They cannot be sued for damages caused by erroneous content. After it came to light that Russia was using online disinformation to sway US (and other nations') elections, many social media companies made voluntary changes. Twitter, which canceled President Trump for his many lies, was then bought by Elon Musk who invited him back. Social media is a free speech "Wild West."

As Nobel Laureate Daniel Kahneman (based on research he did with Amos Tversky) pointed out in his book, Thinking: Fast and Slow, humans are lazy thinkers. Things we hear via gossip from people we know or via social media from people we sort-of know are more top-of-mind compared to dry statistics that we would have to search through incomprehensible journal articles to know. "Top-of-mind" means that we can often recall those "facts" much faster (in milliseconds) than anything we have to actually think about or research. They found that once we remember such "facts," we no longer search for facts that may contradict it. Instead, we usually find reasons to discount contradictory facts. They call this the "availability heuristic" and found it is the single greatest source of error in human decision-making.

Others have found that emotions drive our thinking. The Scottish Enlightenment philosopher, David Hume, famously observed in 1739:

"Reason is, and ought only to be, the slave of the passions and can never pretend to any other office than to serve and obey them"

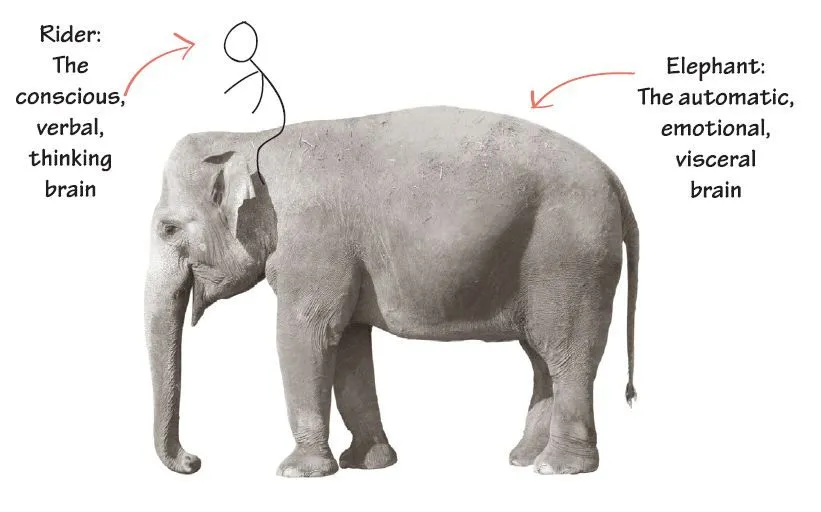

Jonathan Haidt, the social psychologist, in The Righteous Mind, describes human decision-making as an elephant with a small man riding on top. The elephant represents everything that Kahneman describes as fast thinking: our intuitions, emotions, moral underpinnings, subconscious memories, indoctrination in our political, social and cultural milieu, social and sexual evolutionary drives -- things we act on even if we are not consciously aware of them. The little man riding on top represents our intentional thinking, called "slow thinking" by Kahneman. The rider is under the delusion that he is guiding the elephant.

The rider uses reason (and google!) to justify all the elephant's actions. It is going exactly where the rider wanted him to go, or so he believes. The rider can guide the elephant, but Haidt finds that happening less than 10% of the time. We lie, cheat, and justify so well, we honestly believe we are honest. The built-in software that drives our reasoning and googling is called "confirmation bias" by Kahneman. We all have an instinctive drive to confirm our positive self image. Our reason must be consistent with and conform to that image.

Conspiracy Theories

Humans don't like to feel powerless, and actively seek to gain control over our environment and our own bodies. This is why the supplement industry is a $50 billion industry in the US. Cancer patients have been betrayed by their own bodies, so the loss of control is acutely felt. This is why cancer patients are so prone to conspiracy theories that explain why they are ill and why there is no cure for advanced cancers.

Because humans are social creatures, we believe people who we know and like, and don't believe people we don't know or don't like. It used to be the case that fringe theories were only believed by a small number of people. Now, with social media, google and AI, we are confronted by fringe theories we ordinarily wouldn't encounter. If we like those who convey fringe theories (e.g., Joe Rogan is very likeable), we may get caught in a self-justifying epistemic bubble.

People with cancer sometimes believe that there is a conspiracy on the part of Big Pharma and the FDA to keep curative drugs off the market. It has been estimated that the secret must be kept by 714,000 Big Pharma employees plus 18,000 FDA employees. Mathematically, the secret would get out inside of 3.2 years (see this link).

Conspiracy theorists believe that someone in power is preventing the most effective, safest, and cheapest drugs from getting to cancer patients. They believe there is a small number of people who know the real truth and they find the cognoscenti online. Consequently, many cancer patients die each year due to these beliefs. Smart people are perhaps more prone to such paranoid beliefs. Famously, Steve Jobs died sooner because he refused the standard of care. It has been found that cancer patients were 2.5 times more likely to die sooner if they used alternative therapies (see this link). Top oncologists evaluated the information available on social media. They found that about a third of the posts contained mostly harmful misinformation (see this link).

Some of the most widespread myths about cancer now on social media are:

"Sugar makes cancer grow faster.": Based on a little knowledge gained about the Warburg Effect, proponents climb atop "Mt. Stupid" by claiming that they can slow cancer progression by cutting out all sugars from the diet. In reality:

- Prostate cancer prefers to metabolize fats. This is why FDG (Glucose) PET scans usually don't detect prostate cancer, while choline PET scans do.

- Insulin-like Growth Factor 1 (IGF1) inhibitors have had no effect on prostate cancer progression.

- Cancer cells are indeed metabolically active, so active in fact that they will consume whatever food is available - fats, proteins,or carbohydrates. If no free nutrients are available, they will break down healthy cells for food. Cancer cells cannot be starved without killing the person. There is no clinical evidence that they can be starved.

"Ivermectin is the secret cure for cancer." Ivermectin, a anti-parasite drug, gained popularity as the secret cure for Covid-19. Although a large randomized double-blinded clinical trial proved it had no effect on Covid-19. Conspiracy theorists believed Big Pharma suppressed the results. They also believe it is a proven cure for cancer. There is a single clinical trial for its combined use with triple negative breast cancer (for which there are no effective medicines) but there are no trials for prostate cancer. In a pilot trial (without control) of ivermectin+immunotherapy on 8 patients with triple negative breast cancer, 6 had progression, 1 had a partial response, 1 had stable disease, and none had remission.

"Laetrile (B-17/apricot pits) cures cancer." This is one of the most dangerous myths to circulate on social media. It contains amygdalin, which in large quantities, is metabolized into deadly cyanides in humans. While healthy people can probably detoxify the cyanides, people with cancer can and have died (see this link).

"Fenbendazole cures cancer." Fenbendazole is a deworming agent for animals. Based on a single case (Joe Tippens) that has never been duplicated, it circulates on social media as a cure for prostate cancer. There have never been any clinical trials of the drug, only lab studies. Taken orally, it does not reach concentrations necessary to have an effect in animals or humans. It is hepatotoxic.

"Dukoral (cholera vaccine) cures prostate cancer." A Swedish study noticed that men who took this cholera vaccine were less likely to die of prostate cancer. Like all epidemiological studies, it is confounded by selection bias, so one cannot draw any cause-effect relations from it. A follow-up analysis of the same data set, found the same association, in fact, stronger, with all travel vaccines. Men who got travel vaccines were more concerned about health and were also more likely to catch their prostate cancer earlier. It had nothing to do with the cholera vaccine.

"Cancer cures can be found in nature." This is a quasi-religious myth. Some believe that God wouldn't have allowed diseases without also providing cures in Nature. Naturopaths are quacks who treat patients with natural cures. There are no legitimate clinical trials that back up this potentially deadly assertion. There is nothing salubrious about natural foods or medicines. Anyone with a background in the chemistry of natural products (as I have) knows how deadly nature can be and how many thousands of chemicals, innocuous, beneficial and harmful, can be found in "pure" natural products.

Believing the Worst

False negative (called Type 2 errors) are more expensive than false positives (called Type 1 errors). For example, the rustling in the grass may be caused by a tiger; if you don't believe it (negative) and your negative belief turns out to be false (i.e.' there is really a tiger), then you are dead. However, if you do believe it, and it turns out to have been the wind (i.e., a false positive), you may feel foolish, but you won't be dead. This is called "negativity bias."

Therefore, humans are programmed by evolution to believe things that we imagine but cannot verify. Imagining future negative outcomes without adequate evidence is part of human mental equipment. We instinctively believe the warnings of our trusted social group.

Randomness/Statistics are Difficult to Comprehend

Dealing with randomness is emotionally difficult. Statistics (frequentist and Baysian) are incomprehensible to most people. Frequentist statistics rely on sample size to increase the probability that a hypothesis is false. There is never certainty because the chosen sample always has some possibility of being different from the entire population. As sample size increases, our confidence that it is a representative sample increases, and the probability of error decreases. With Baysian statistics, prior odds affect posterior odds. Someone well-versed in statistics may understand what a study means or doesn't mean, but someone new to the field is liable to misinterpret them.

Humans are always hunting for patterns. If a tiger appears even some of the time that the grass rustles, we will always look for a tiger when the grass rustles. We find patterns even where there are none. We filter out "noisy" data to find signals even if there are no signals (see Kahneman - Noise: A Flaw in Human Judgment). In an important mathematics proof this year by Sarah Peleuse at Oxford , she found that any chosen subset of random numbers will display a pattern even if only small subsets are chosen. We see patterns even if there are none.

When faced with statistics whose meaning is difficult, a typical reaction is "they can prove anything with statistics" or "it doesn't apply to me." Those who don't understand "levels of evidence" and grade, can certainly be fooled by statistics. Zaorsky et al. showed that common statistical techniques called "propensity score matching" or "inverse probability weighting" can be finagled to arrive at opposite conclusions from the same retrospective observational study. Similarly, Wang et al. showed that the analytic method used in diet studies could change red meat from having a positive effect on longevity to a negative effect (also, see this link). Others have shown that prior to 2000, journals allowed "p-hacking," specifying what the primary outcome should be after the research was analyzed. Post-hoc definition of sub-groups can lead to comical results. As a result of such problems, all major peer-reviewed journals have changed their standards. It's a work in progress, but it's improving.

For those who think the findings don't apply to them, they may be right. Clinical trials have very strict definitions of inclusion and exclusion criteria. The outcomes of such a trial may not apply to those who do not meet those criteria. Outcomes are conventionally reported as a median (the halfway point) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) around it. The size of the 95% CI is the result of both the statistical variance due to sample size and the natural variance among patients. For large sample sizes, most of the variance is natural variance. It is possible that a given patient falls outside of the 95% CI, but is highly unlikely. If one were to wager a bet, the median would be the best guess.

Logic Deceives Us

With imperfect knowledge, logic can deceive us. For example, Huggins and Hodges discovered in 1941 that testosterone is necessary for prostate cancer to grow. By turning off testosterone completely, prostate cancer progression can be slowed. "Logic" dictates that giving untreated men testosterone would cause progression. That turns out to be wrong much of the time. Morgentaler found that a man's androgen receptors are fully saturated at very low levels, so adding more has no effect and may even be useful in some cases. Human biochemistry is very complex (and different from mouse biochemistry!). We never fully understand human biochemistry, so always have imperfect knowledge. As far back as Aristotle, it has been known that inductive reasoning cannot be proved. Yet humans engage in inductive reasoning all the time.

We often rely on Occam's razor to make judgments. It says that all things being equal the simplest explanation is the best. But what if all things are not equal, or we just don't know if all things are equal?

"Levels of Evidence" and GRADE determine why a trial or review is dispositive

The neophyte climbs "Mt. Stupid" rapidly because he doesn't understand why one study is better than another. Only a large replicated well-done randomized clinical trial is beyond question. For a description of what constitutes a "well-done" trial, see: Systems for grading the quality of evidence and the strength of recommendations. For a list of what are the agreed upon levels of evidence, see: The Levels of Evidence and their role in Evidence-Based Medicine. All but Level 1 Evidence, that is, all observational studies are subject to confounding by "selection bias." Google and AI searches do not make such distinctions, which explains why their conclusions are usually wrong.

Dr. Google/YouTube

In 1998, Google became the most popular search engine for the Internet. It watched individual's searches and learned what each person was most likely to search for. It also looked at people who did similar searches. It democratized knowledge, but created epistemic bubbles. While it can be used to find information outside of the kind one's peer group looks for, it prioritizes the kind of information one and one's peer group has already looked for.

Google provides lots of information, but doesn't put it in useable form. It leaves it to the person to form that information into knowledge - the understanding and application of the information. It makes no distinctions about which studies are good or bad. A mouse study may be listed behind a prospective randomized clinical trial if the search terms are in the abstract.

I asked Google the same question about salvage radiation asked of ChatGPT below, and it did not come up with any of the three randomized clinical trials or their meta-analysis that patients should be making informed decisions based on.

In 2006, Google bought YouTube. YouTube videos on medical issues are particularly insidious. Because one sees the "doctor," the availability heuristic kicks in, building trust faster than reading a dry journal article with statistics and terminology one may not understand. The presenter often wears a white coat to create trust.

- There are seldom legitimate sources given for what is said;

- There is seldom a discussion of any controversial issues; and

- The presenter's qualifications are often not included.

There are ways of doing a video presentation right, but many patients will not be able to distinguish misinformation from good information.

ChatGPT gets one to the top of "Mt. Stupid" faster

In 1975, researchers came up with a new method for compiling a lot of studies on the same topic. One always has more confidence in trials that have been replicated with similar findings and a review and meta-analysis is always a higher Level of Evidence than a single trial. Cochrane Reviews is the top journal for publishing such meta-analyses.

To review multiple studies, the authors must go through the following steps:

- Define the research question as narrowly as possible, but not so narrow that only one trial is included. The question should include the relevant patient population and the problem examined, the intervention used in the trials, what it is compared to, and the which outcomes are used to evaluate the trials.

- Sources are chosen according to universally agreed upon quality. All reviews use the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines. PubMed is perhaps the most used PRISMA source.

- Data are extracted from the sources in accordance with the question asked.

- The eligibility of the extracted data is assessed.

- The data are analyzed and combined. The analysis provides a hierarchy of reliability based on such quantitative and qualitative assessments as the sample size and how well the trial was conducted. The combination is often summarized in Forest Plots showing confidence intervals.

For anyone interested in a deep dive, here is the latest Cochrane Review Handbook.

In the last couple of years, machine learning algorithms that provide summaries in comprehensible language have gotten popular. All of the above issues still plague it. Unfortunately, it is called "artificial intelligence." Intelligence implies that it knows what it is spewing forth and wisely selects that information. It does neither.

- It simply scrapes information from a popular variety of sources and provides a plain language summary very quickly.

- It has no judgment -- results of lab studies may have the same salience as Level 1 evidence. As Hume observed (above), emotions are required for reasoned judgment, and AI will never have that.

- More recent trials are lumped together with older, no longer relevant studies.

- The output is only as good as how the query is phrased, and what is currently most popular in searches.

- It is insidious, because it sounds better than the raw data.

- One cannot check the reliability of its sources.

I have found it is wrong more often than it is right, but it always sounds authoritative, and is therefore more dangerous than mere google searches. It only helps one climb to the top of "Mt. Stupid" faster.

"Intelligence" is the ability to acquire and apply knowledge. Intelligence can be used to obfuscate and lie. Conversely, intelligence, if selective (and it is always selective) can be used to delude ourselves. "Truth" is quite different. AI provides intelligence, not truth.

Here's an example:

I asked ChatGPT a frequently asked question:"How do I decide when I should have salvage radiation therapy after a prostatectomy?"

ChatGPT said:

The Solution: Science and Experts

The solution to the problems in acquiring trustworthy information is "science." Science is a social construct whereby hypotheses are tested and a community of experts decides, provisionally, what truth is. It is provisional because science can later be proved to be wrong. It depends on having lots of hypotheses that may be falsified and usually are, and is only as good as the hypotheses tested.

For a fuller discussion, see: The Constitution of Medical Knowledge.

A patient goes to his doctors for their expertise. But doctors should be able to patiently explain why the suggested protocol is as it is. While many patients and doctors prefer a paternalistic decision-making model, there will be fewer regrets and recriminations if they engage in shared decision-making.

For a discussion of shared decision-making, see: Managing the Doctor/Patient Relationship.

All of the above should serve to let you know that you may be wrong in spite of clear instructions from Dr. Google, YouTube, or ChatGPT. I don't expect patients will stop using those readily available tools -- that genie is out of the bottle, but it should lead one to question that "knowledge."

Sometimes you will come across a research study online that seems perfectly relevant to your case. How should you handle it with your doctor?

- The way I do it is, first of all, respectfully.

- I start by acknowledging that he probably has seen it or better information.

- My approach is collaborative and open, rather than confrontational and closed-minded.

- I try to share it, preferably via email, before my visit, if one is coming up. This gives him a chance to look at it and respond to it in a more considered way.

- I am also careful about sources. I would never send some “miracle cure” from a random Internet site. The articles to be discussed are always based on peer-reviewed medical evidence in highly-regarded journals. One can see if the study is highly-regarded if the study has had many citations in Google Scholar. Peer-reviewed journals all have an "Impact Factor" that shows how often articles in that journal are cited. The Lancet, the New England Journal of Medicine, and the Journal of the American Medical Association always have the highest Impact Factors.

- I am also open to refutation: I may not have understood why that case does not apply to my case;

- I may not know that there are more recent findings, possibly from a higher level of evidence; or,

- I may have misunderstood the findings or conclusions.

The only way to avoid "Mt. Stupid" is to have humility. Most attending doctors at teaching hospitals are experts in their fields. The empowered patient will tap into their expertise.